Perspectives

The Wealth of a Nation

January 2026

- Kenichi Ohmae, author and former professor and dean of UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs

Kenichi Ohmae, the Japanese strategist who predicted globalisation before it had a name,

spent three decades making an argument that most economists found discomfiting: that the

economic destiny of nations is shaped not by governments or central banks, but by

consumers. Regions that generate their own demand, he argued, will always matter more

than the administrative or judicial borders drawn around them. In the early ‘90s, Ohmae

even predicted that Bangalore would emerge as the silicon valley of India; clearly a

winning forecast.

From Collateral to Capital

In the summer of 1991, India was weeks from sovereign default. Foreign exchange reserves

had dwindled to three weeks of import cover. Under extreme secrecy and in the midst of a

general election, the Reserve Bank airlifted 67 tonnes of gold (47 tonnes to the Bank of

England & 20 to the Bank of Switzerland) as collateral for a $600 million emergency

loan. The news leaked and triggered public outrage with the image of a nation pawning

its gold to keep the lights on becoming one of the most humiliating episodes in India’s

post-independence history.

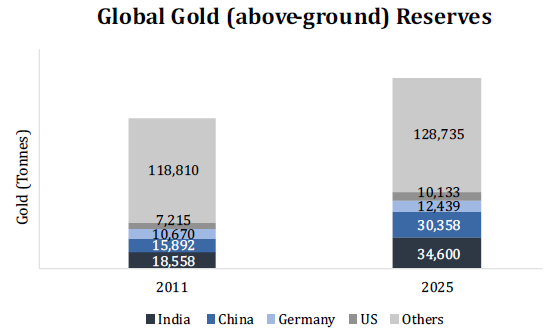

With 2/3rds of the current Indian population having been born subsequent to the nation’s

most embarrassing moment, circumstances are dramatically different. Today, India holds

approximately 34,600 tonnes of gold across central bank reserves, temples, and

households. That is roughly one-sixth of the world’s entire above-ground stock, and the

number keeps growing as India consistently accounts for ~25% of global demand. At

current prices, the total value of gold held by Indians exceeds $5 trillion which has

doubled in the past year driven primarily by geopolitical factors. The value and

appreciation in this gold stock overshadows the entirety of India’s GDP, trade deficit

or any other economic metric one were to consider. From the brink of collapse, India’s

population is now quite literally sitting on a gold mine. The difference is that they

built it themselves, one wedding, one harvest, one Diwali at a time.

The per-capita arithmetic makes the point sharper. Average income is ~$3,000 whereas

per-capita gold holdings work out to ~$3,600. On average, Indian households are sitting

on stored wealth equivalent to ~15 months of national income, exceptional for any

economy, let alone one at India’s stage of development.

India’s external balance sheet tells a consistent story. External debt stands at ~$746

billion while the foreign exchange reserves are ~$700 billion. India can cover nearly

its entire external debt from cash reserves alone, with one of the world’s largest gold

positions untouched. From pledging gold to emerging as a modern El Dorado, India’s

transformation is not a financial oddity. It is a reflection of the grit and savings

culture of modern India.

Distributed, Not Divided

Ohmae’s deepest insight was that within any large economy, multiple self-sustaining

regions (ie: Economic Regions) are key to creating robust and sustainable national

prosperity. The answer lies not in the mathematical mean but rather in the distribution

of wealth

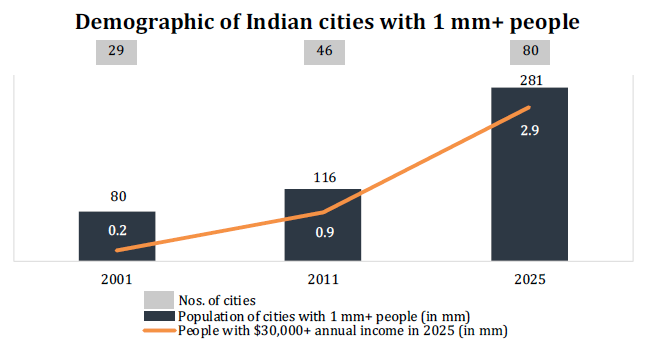

India’s economic gravity has been shifting away from the traditional four metro cities

for two decades now, and the pace is accelerating. Cities with populations exceeding one

million have expanded from 29 in 2001 to an estimated 80 today. Their combined

population has more than tripled, from around 80 million in 2001 to 281 million in 2025,

effectively adding the equivalent of more than 200 San Franciscos. These major urban

centres are not dormitory towns feeding the metros. Each is developing its own gravity:

distinct industries, locally generated capital, and consumption patterns that do not

rely on Delhi or Mumbai for permission.

The income data reinforces the urbanization trend. Individuals earning above $30,000

annually (ten times India’s per-capita income), have grown fifteenfold (adjusted for

inflation), from under 200,000 in the early 2000s to nearly 3 million in 2025.

Increasingly, these “super high earners” are found in cities like Surat, Indore,

Coimbatore, Ludhiana, & Rajkot, generating wealth from varied industries such as

diamonds, textiles, agro-processing, etc.

Beyond the Metros

The clearest evidence of the shift away from metro-centric growth is in what people are

buying, and where.

Aurangabad is the 9th most populous city in Maharashtra and the 37th most populous in

India. It is best known for the UNESCO-listed Ellora Caves carved centuries before Jesus

Christ was born. On one single day some years ago, a group of businessmen, farmers and

doctors collaborated to negotiate a bulk order of 150 Mercedes-Benz vehicles at one

shot. This was not a fleet deal but rather a reflection of local aspirations as well as

their heft in discretionary consumption capabilities. Mercedes now operates roughly 100

showrooms nationally and is investing $20 million to add 20 more outlets in markets like

Jammu, Patna, and Kottayam. Similarly, Domino’s Pizza now operates 2,000 outlets across

421 cities and plans to double this count in the next few years. These companies are not

undertaking charitable expansions. They are following the money.

What distinguishes this cycle from earlier phases of India's growth is premiumisation:

consumers are not just buying more, they are buying better. The pattern extends well

beyond automobiles and pizza.

- Smartphones: 50% of Apple volumes now come from non-metro regions. Over 70% of phones ordered on Amazon are delivered to Tier II and III cities.

- Home Appliances: E-commerce platforms like Amazon report that over 65% of electronics sales now come from non-metro regions.

- Apparel and Beauty: Premium beauty and personal care products are gaining rapid traction beyond metros, with ~55% of Nykaa’s (a cosmetics e-commerce platform) premium and luxury beauty sales coming from non-metro cities, fueled by a blend of global glamour and local aspirations.

- Air travel: India’s domestic aviation growth has decisively shifted beyond the metros. In 2016, nearly 70% of all air travel was to and from the top eight metros. By 2025, this share has declined to just 33.2%, highlighting the rapid rise of Tier II and Tier III routes driven by regional connectivity and rising aspiration-led demand.

Importantly, broad consumption is not generally funded by government subsidy or borrowed

capital. These cities operate on locally generated cash flows, high household savings,

and reinvestment within the regional economy. In Ohmae’s terminology, they are

region-states; economic units whose prosperity is determined by their own consumers

rather than solely reliant on central policy.

The Per-capita Ruse

GDP per capita tells you the size of the pie attributable to each person but does not

reveal who consumes the pie.

Take the example of Turkmenistan. It reports a per-capita income of approximately

$10,800, more than three times India’s and comparable with Malaysia or Brazil. On paper,

the average Turkmen citizen should be relatively prosperous. In practice, the wealth

sits with a narrow elite connected to the gas trade. Public services are limited,

economic opportunities are restricted, and ordinary citizens lack reliable access to

basic essentials. The per-capita number tells you almost nothing about the quality of

their lives. High averages can mask hollow distribution.

India’s trajectory is structurally different. Its strength rests not on a thin layer of

ultra-high earners or a single economic engine, but on the steady accumulation of wealth

across millions of households; a consumption base that is durable, repeatable, and far

less exposed to the external shocks that periodically derail concentrated economies.

The Golden Road

- William Dalrymple, highly acclaimed historian and bestselling author of The Golden Road

Thousands of Roman gold coins, notably aurei and denarii, dating as far back as 30 BC have been discovered across India. From time immemorial, Indians have mined limited amounts of gold but have successfully alchemized trade and savings into a durable consumption engine. This distributed prosperity is now being recognized at the policy level. In the latest budget announced on February 01, 2026, the Indian Finance Minister announced a shift towards investing in a number of Economic Regions rather than individual cities, with $600 million allocated per region over five years. In a nod to Ohmae, this announcement formally acknowledges that India's economic future lies in building self-sustaining regional ecosystems.

The India opportunity is not about one city, one sector, or one policy cycle. It is about the breadth and depth of a consumption base that is, quite literally, built on gold.