February 2024

The Economist's disdain for India's Prime Minister is not breaking news. Before the 2014 general elections, when Modi and the Bharatiya Janata Party ('BJP') first came to power, the publication endorsed his primary opponent, Rahul Gandhi, because "it would be wrong for a man who has thrived on division to become prime minister of a country". However, Modi being a divisive leader is also not breaking news. Depending on one’s political ideology, he has either restored India to its rightful place in the world order or has led a religious charge against human and minority rights thereby wrecking the social fabric in the world's largest democracy.

The divisive role of religion in politics is neither new nor unique to any one country or point in time. Yet, we submit that self-interest will dictate how people will vote. Even in the United States, where lines between Church and State have blurred beyond recognition due to politics, slogans around making America great again are really platitudes appealing to voters' self-interest. As the immutable law of psychological egoism has illustrated, we believe that a majority of the two billion people around the world (~25% of the global population) voting in elections this year will let financial report cards dictate their electoral mandates, rather than altruistic considerations.

The longest side of the triangle

If one imagines a country's economics, politics, and religion as a right-angle triangle, we posit that economics forms the hypotenuse, i.e., the longest side. The disproportionate weightage towards economics, however, does not diminish the role of politics and religion to a country's citizens. Tribalism perhaps best defines a large part of politics today, with an 'us-vs.-them' mentality casting its shadow over international relations.

Political wars have intertwined with religion, often in strange and eerie ways. Benjamin Netanyahu, for instance, has invoked ancient Jewish scriptures when commanding troops and voters to lay waste to Gaza which, ominously, was known as 'Tell es-Sakan' or 'Hill of Ash' at the time that Moses proselytized in that region. Ukraine, where Russia's invasion has destabilized the world's political order, protested by re-calendarizing Christmas from the Russian Orthodox Church’s January date to December 25th – so much for religious clarity!

India is not immune to the intermingling of religion and politics either. One of the BJP's biggest electoral planks over the last three decades has been constructing a temple in Ayodhya, described by some as Hinduism's version of Mecca or the Vatican. While the faithful have already contributed over $420 million to the temple, political watchers predict that the January 22nd inauguration has cemented Modi's ascension to a third successive term at the helm of Indian politics.

Near the temple, however, also sits a new government-funded airport, a massive, redeveloped railway station, and plans for a township including residential complexes and shopping centers. Jefferies, a brokerage, estimates that infrastructure investments in the holy city can result in it attracting up to 50 million tourists annually, up from barely 0.2 million in 2017. If these numbers are achieved, Ayodhya would become one of the world's top tourist destinations rivalling New York City and ahead of Thailand or Paris. The resultant economic stimulus would suggest that the Modi government understands that politics and religion are not the longest side of the triangle.

The voter's report card

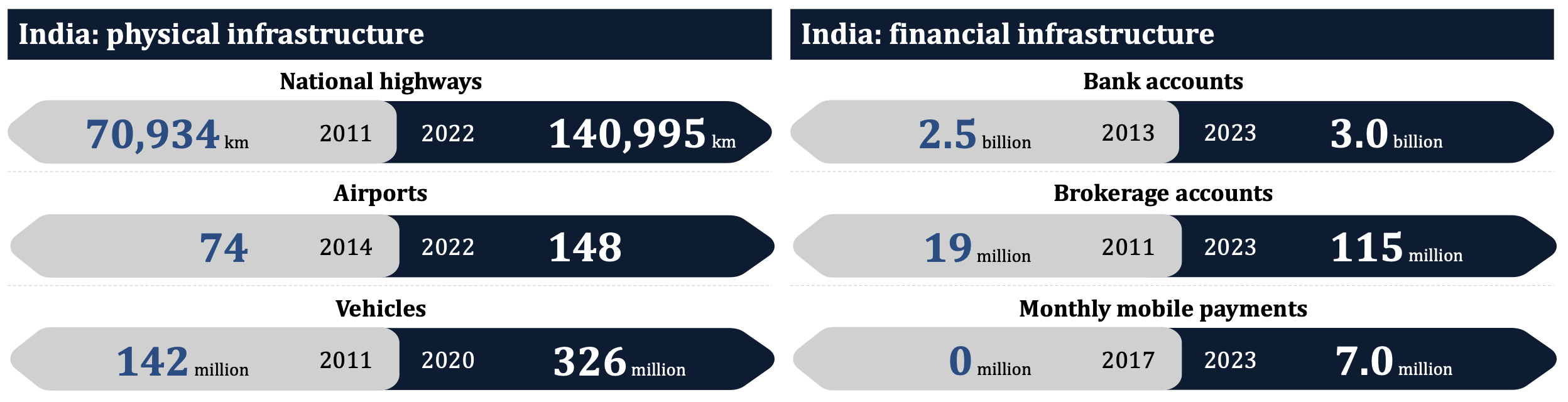

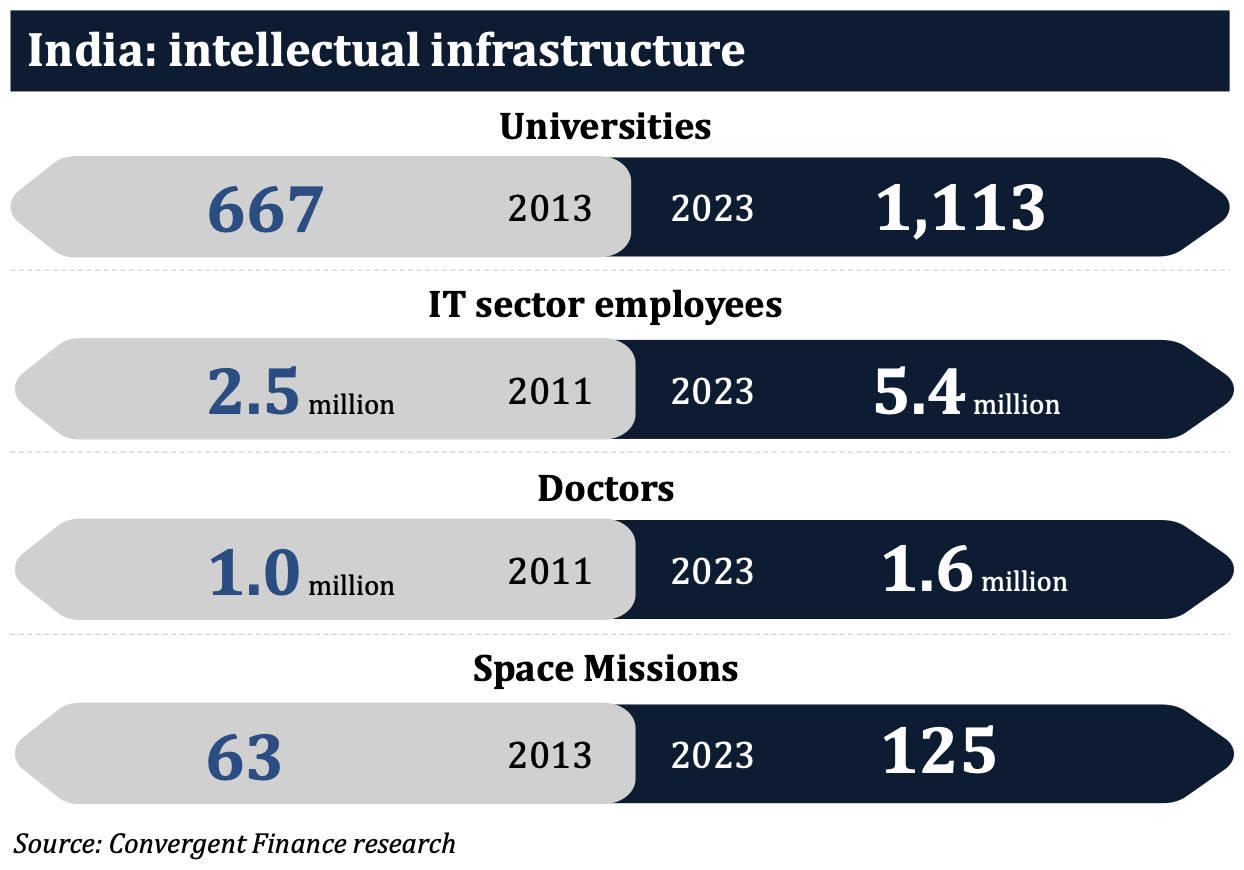

In the past decade since Modi first came to power in 2014, India has experienced increased economic output, higher incomes, and rising consumption. We believe these improvements have resulted from a targeted focus on developing three types of economic infrastructure: physical, financial, and human.

With regards to physical infrastructure, the government has invested heavily to improve the movement of goods, services, and travelers across the country. A doubling in the length of national highways between 2011 and 2022 has led to increased throughput at India's ports, where turnaround times for ships have improved by ~60% to ~2 days. A similar doubling of the number of airports in the country in the past decade has resulted in overall air passenger traffic growing from ~61 million in 2013 to nearly 400 million by March 2024, thus reducing friction in human throughput to ports, remote locations, and urban centers.

When the economic calculus of the infrastructure buildout combines with India's vast, skilled talent pool, we see wealth and consumption effects kicking in. The country's position as the world's back office – there are now over 1,600 centers supporting over 3 million jobs – is helping nudge per-capita GDP towards middle income levels, with the figure expected to double to $5,200 by 2030. The number of people earning above $10,000 annually is also expected to increase ~4x to 100 million by 2027; this elite group will match the GDPs of Saudi Arabia or Switzerland.

A larger number of wallets – and their thicker nature – have resulted in increased consumption of discretionary and luxury items. For example, Domino's Pizza's India franchise has grown to from 586 outlets to over 1,800 in the past decade. In the same period, revenues for Titan, which operates India’s largest jewellery brand, have grown from ~$1.9 billion to ~$5.0 billion.

Domestic consumption has been supplemented by extraneous events benefiting India. Hawkishness over China, compounded by Covid-19, has resulted in countries adopting a 'China+1' approach. Since 2016, India's goods and services exports have grown by 10.1% annually, with outbound trade expected to touch ~$900 billion this year.

Tuning out the noise

Increasing prosperity does not unilaterally imply that all is well. Inequality remains a problem, with the top 10% of the population constituting ~57% of income. There is disquiet among sections of the population given the increased tilt towards right-wing politics. Minorities are fearful and anxious. Consequently, the BJP is yet to make any inroads in several southern states with significant Muslim or Christian populations.

Yet, it is also a fact that India's robust economic performance has contributed significantly to the Prime Minister's 76% job approval rating. The fact that the BJP retained or took power in 5 out of 9 state elections last year (representing ~23% of India's population) is a potential lead indicator of their likely success in general elections.

Around the world, politicians of different (and sometimes extreme) ideologies are embracing the timeless dogma: "When all else fails, common sense prevails." In Turkey, Erdogan finally appointed Hafize Erkan as Central Bank Governor after experimenting with five candidates in five years, including his son-in-law. On the day of her appointment, Hafize raised interest rates from 8.5% to 40.0%, prompting austerity but also earning accolades. In Argentina, Javier Milei who is as right-wing as they come, swept the Presidency on a platform of abandoning the peso and dollarizing the economy. In the US, American voters continue to cite the economy as their core concern heading into the 2024 elections, thereby explaining Trump’s landslide success thus far in the primaries.

While religious and political considerations slightly counterbalance our view that economics will decide elections, we feel confident in saying that voters will tune out the noise and cast their ballot for the most appealing economic outcome. Rahul Gandhi, Modi’s fiercest critic, appears to agree with our view based on his candid admission above!

Back to perspectives