February 2023

In 2022, Morocco, a country that struggled to qualify for the FIFA World Cup over the past 50 years, defeated heavyweights Portugal and Spain to become the first African team to reach a World Cup semi-final. The seeds for Morocco's 'overnight success' were sown in 2009 when $80 million was invested in launching the Mohammed VI Football Academy. Under the leadership of coach Walid Regragui, Morocco promoted football as a national priority and trained players who excelled at European clubs before coming to represent their country. There is more to learn from the Atlas Lions than stellar football – how long-term planning can generate extraordinary dividends.

We believe that similar long-term planning is underway in India. In September 2014, immediately after Narendra Modi came to power, the government announced the 'Make in India' program to spur capacity creation in traditional and emerging sectors. Aided by a stimulus scheme offering companies cash and incentives linked to production, sales, and expense targets, it is undeniable that the Make in India program has resulted in a capex (capital expenditure) 'super-cycle.' Unlike a 90-minute football match, however, this capex super-cycle is a multi-decade play readying India for long-term domestic growth and a more significant role in the global economy.

Capex: a launchpad for growth

Enhanced capex across the economy is expected to generate enormous dividends for the country. Consumption and exports across a range of manufacturing and service sectors have differentiated India from other hubs (e.g., Vietnam) that specialize in manufacturing narrower categories of goods. Hence, it is not surprising that Morgan Stanley predicts India's gross domestic product (GDP) to grow to ~$8 trillion by 2031 from ~$3.3 trillion in 2022 and total exports to grow to ~$1.9 trillion by 2031 from ~$670 billion in 2022.

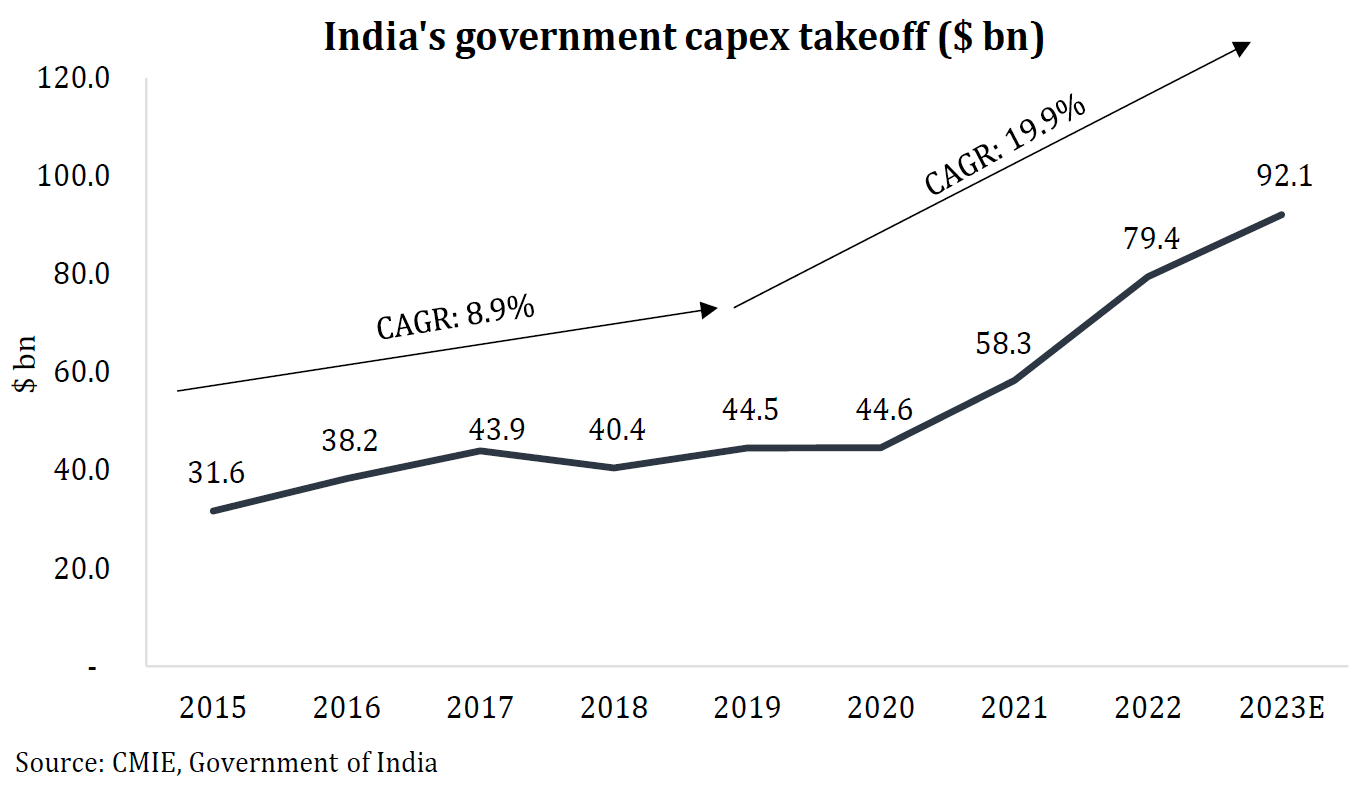

Roads, railways, and ports may not appear glamorous examples of a capex super-cycle. However, such investments are prime drivers of the Indian government's ~$92 billion capex spend for 2023 (a whopping ~192% jump from 2015). Over the last two years, India's highways authority has laid down enough roads to cover ~80% of the Earth's 40,000-kilometer circumference – making for one arduous road trip!

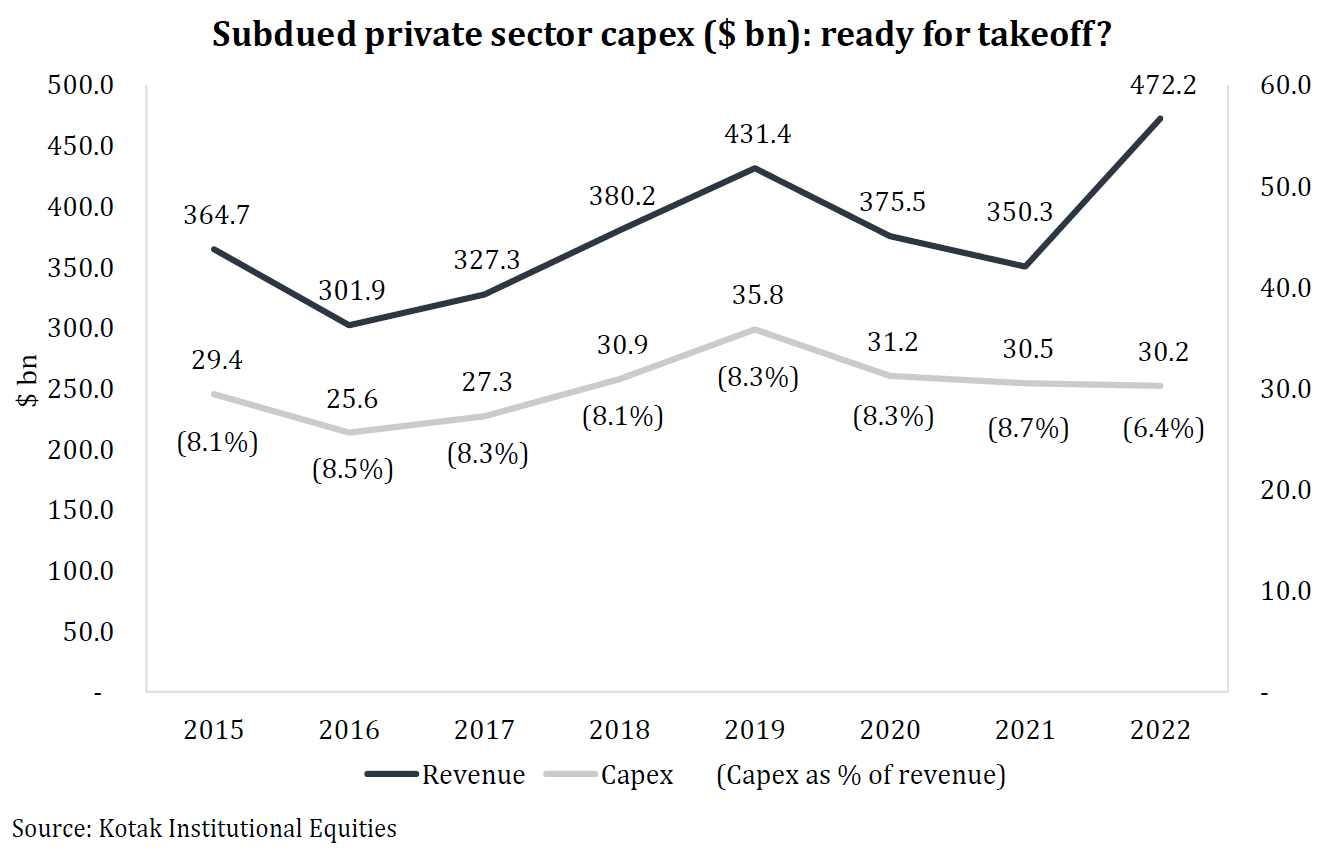

Ideally, India's private sector should be driving down the roads laid by the government. However, companies listed on the NIFTY Manufacturing Index have spent much less than the public sector on capex, leading to appeals by the government for the private sector to increase spending. While private sector capex has stayed somewhat consistent at ~8% of revenues, the scale of mega project announcements in recent times bodes well for a surge in spending in the coming years.

Consistent with India's increasing export orientation, manufactured goods are finding their way via India's roads to its ports, from where 95% of the country's trade takes place. Previously weighted towards lower-value dry bulk exports (e.g., metals, grains), India's ports have actively shifted towards containerized trade as shipments of high-value goods increase. In 2021, India's ports handled ~16 million containers, up ~65% over the prior decade. Scale and de-bottlenecking have resulted in efficiency. Since 2011, turnaround times for ships have improved by ~60% to 2 days, while cargo volumes have increased by 40%.

Tax incentives designed to facilitate manufacturing are augmenting the government's other initiatives. A concessional tax rate (15% instead of 25%) is being offered to new manufacturing entities, while the corporate tax rate was reduced from 30% to 22% two years ago. However, the true ace in the deck has been a government scheme, first introduced in 2020 amid lockdowns, known as production-linked incentives (PLIs).

Production-linked incentives: the multiplier effect

The PLI schemes aim to stimulate businesses to build/ expand production capacities of critical products expediently. Incentives, mostly by way of subsidies and cash rebates, are linked to achieving revenue, capital investment, or expense targets. Non-cash incentives include tax rebates and expedited acquisition of land.

The scheme for the textiles sector, for example, aims to boost India’s competitiveness in the global apparel and fabrics industries. A company will have to show a minimum capital investment of ~$36 million and a turnover of ~$72 million in the first year to receive an ~$11 million incentive (i.e., 15% of turnover). Annual sales must rise by 25% for the company to continue receiving the subsidy.

PLI schemes are like lottery tickets with multiple winners. With a total allocation of ~$35 billion (~1% of India’s GDP) spread over 5 to 7 years, PLIs aim to reduce the country’s imports, increase its exports, and promote higher research spending. The schemes are expected to create 3 million new jobs while adding ~$500 billion to manufacturing output by 2027 (2021 output stood at ~$447 billion).

Key objectives: imports, exports, and research

Import substitution: Production-linked incentives are encouraging upstream integration, thus increasing India's appeal as a production hub. By extension, they will also reduce the country's dependence on imports. Encouraged by schemes specifically announced for active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs), companies are starting to produce 35 of the 53 APIs that India currently primarily imports from China, as manufacturing costs in India are ~25% higher. Aided by PLI incentives, India's imports are expected to drop to ~45% by 2024.

Export competitiveness: It took two world wars for the United States and Japan to become electronics powerhouses before gradually ceding ground to China in the post-Cold War era. India has leveraged the current geopolitical environment to quickly retool and become a meaningful supplier. December 2022 witnessed a landmark as Apple became the first to export $1 billion of smartphones from India that month. Apple's contract manufacturers, Foxconn, Pegatron, and Wistron, are all beneficiaries of PLI schemes. In the new paradigm of 'friend-shoring' and intellectual property security, global companies have leveraged PLI schemes to build capacities that did not exist two years prior. Samsung is also building the world's largest phone production facility near Delhi, representing 29% of its global production at a single location.

Research and development (R&D): PLI schemes also focus on increasing overall R&D spending in India (currently at a mere 0.7% of GDP). A ~$9 billion program for semiconductors, introduced in late 2021, has tied incentives to design expenses and the number of chips deployed in end products. Companies have announced $25 billion of semiconductor investments, indicating a chipper outlook for the sector's future.

Critics argue that PLI incentives benefit capital-intensive sectors (e.g., semiconductors) and won't be able to create enough jobs for a large labor base that needs to rotate toward service industries. Questions have been raised on whether incentives alone are sufficient to attract and retain supply chains in India; perhaps companies will move elsewhere once the scheme expires. Our submission, which Lee Kuan Yew certainly subscribed to, is that 'Rome wasn’t built in a day'. India's vision and execution in recent times at least seem to be laying a foundation.

Foundation for the future

The most successful people (or institutions or nations) all play the long game. This long game doesn't necessarily attract a lot of attention or win quick accolades. Each incremental but modest step forward may go unnoticed, until eventually success becomes too obvious to ignore. Rome wasn't built in a day, as they say.

India has been working towards better infrastructure, at the cost of short-term convenience, without taking its eyes off the long-term target. It has invested at record levels, increasing output, turbocharging exports, and streamlining domestic supply chains. We are hopeful that the foundation that emerges culminates into a dream run for the Indian economy – much like that of the Moroccan football team.