Perspectives

Reality is not what it seems

May 2024

- Carlo Rovelli, highly acclaimed theoretical physicist and author

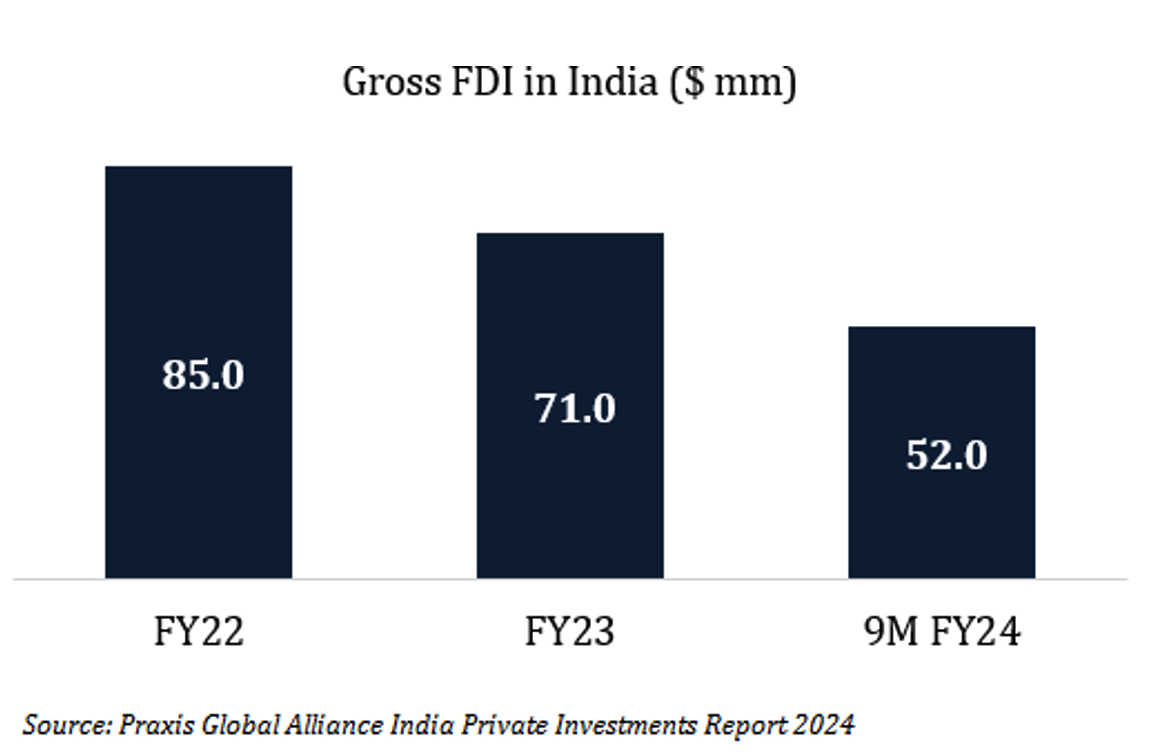

It has been observed repeatedly, by practitioners ranging from physicists to psychologists, that reality is routinely different from popularly held wisdom. Lately, few narratives have garnered as much attention and optimism as the "India story". With its vast market potential, burgeoning tech and manufacturing sectors, and a demographic dividend poised to drive growth, India has been hailed as an economic powerhouse on the rise. However, this compelling elevator pitch has not translated into stronger foreign investment inflows thus far. In fact, many strategic and financial investors alike have been withdrawing from the country. Therein lies a paradox that is worth unraveling.

Does deglobalization explain this paradox?

The East India Company, founded in London in 1600, can rightly be identified as the first truly multinational corporation. Subsequent waves of globalization remained Western-centric, with companies from the United States and Europe setting sail to capitalize on opportunities in emerging markets. However, as one seafaring scribe once said: "When the winds of life blow hard and hit your boat, you've got to adjust your sails to keep afloat." The once aggressive conquistadors of global capitalism are now exhibiting signs of defensiveness and retrenchment.1

An obvious factor, amidst economic and geopolitical challenges, is that many companies are refocusing on their home markets. With inflationary pressures omnipresent, the US Federal Reserve has tightened liquidity and maintained a target rate in the range of 5.25% to 5.50%, resulting in increased interest costs for highly leveraged US companies, as well as outflows from global equities. An additional temptation arises due to the glaring valuation differential, with Indian subsidiaries routinely commanding higher valuations than their parents.

The difficulty in managing businesses remotely, exacerbated by management gaps at headquarters, further compounds the challenges faced by foreign companies operating in India. In the automobile sector, for example, several manufacturers, including Ford, General Motors, and Harley-Davidson, are withdrawing from the Indian market, primarily due to their inability to adapt to a rapidly evolving local market driven by changes to the retailing system as well as a move towards electric. In contrast, Indian automobile giants like Mahindra and Mahindra, Tata Motors, and Maruti Suzuki are setting new sales records every year, underscoring the strength of the domestic market. Regulatory compliance has also been a challenge for many multinationals, particularly those with high levels of "value addition" from headquarters (aka: micromanagement). In banking for instance, foreign lenders have struggled due to competition and differences in regulatory and compliance guidelines. In 2023, Citi Bank sold its India operations to Axis Bank. Barclays, HSBC and Bank of America have all downsized significantly. In 2023, Holcim sold its Indian operations to the Adani Group which is now targeting 20% cement market share by 2028. Metro AG also sold its Indian business to Reliance after 19 years, stating that "Due to the increasing market consolidation, accelerated digitalisation and intense competition, Metro India operations would not fit Metro's core growth strategy in the future." How ironic that cement and retail majors with decades of operational expertise globally and in India, both sold out to local groups who lacked any prior experience in these sectors.

What does this mean for the Indian market?

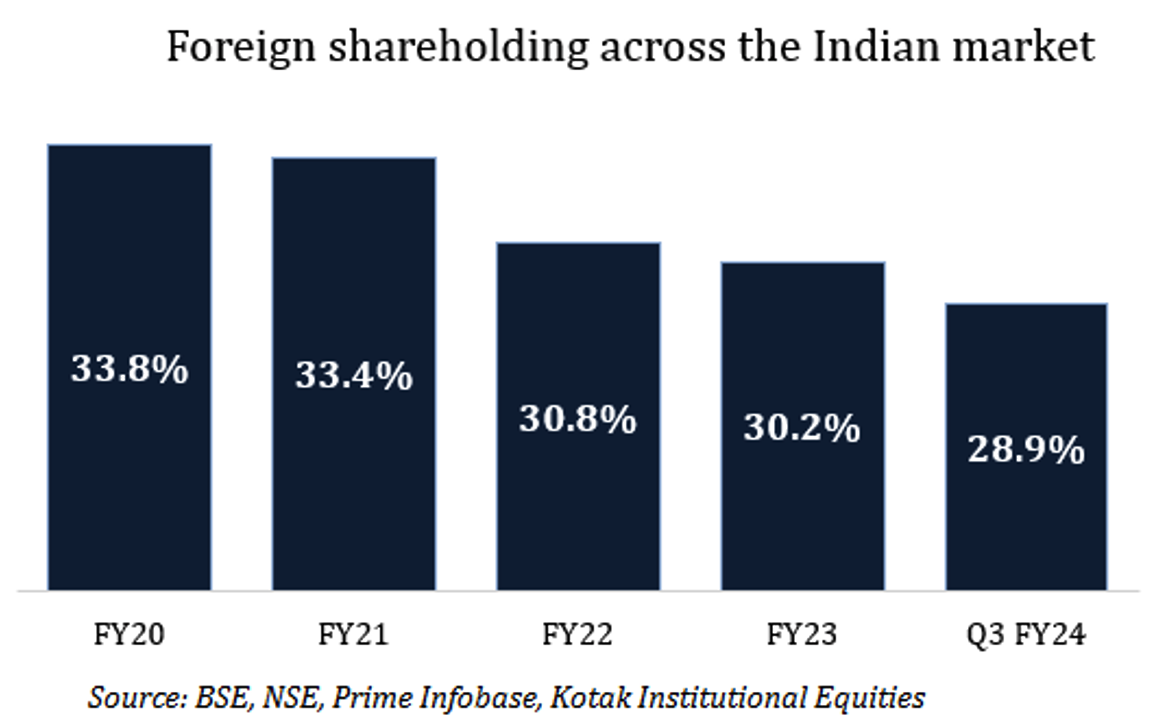

As Western investors vacate the market, Indians are picking up the slack with much glee! 2023 foreign investment outflows from the stock market were mostly compensated by Indian mutual funds who have all seen swelling assets2. Over the last 10 years, domestic institutional holdings have been on the rise; in NSE-listed companies, they went from 10.49% in 2013 to 15.96% in December 2023.

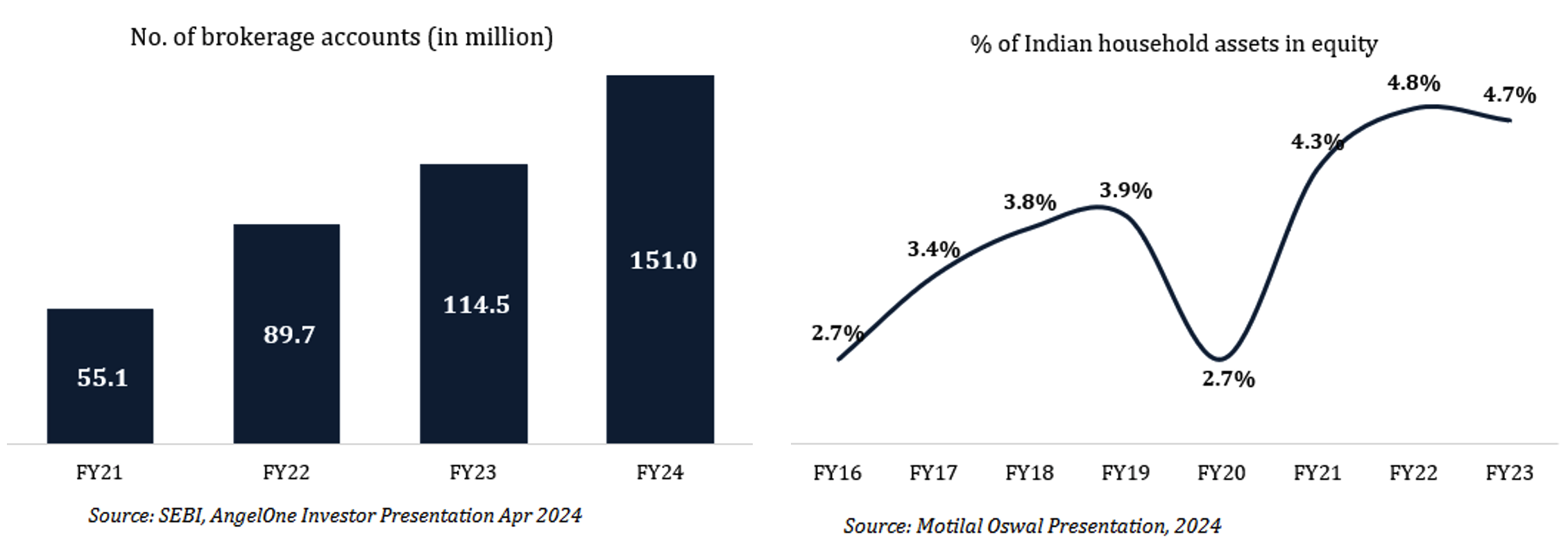

However, the biggest force to reckon with has been the retail investor. In the equity markets, this can be witnessed by the steady increase in the number of brokerage accounts opened every year, with an increase in momentum since 2020 as affluence levels continue to rise, and interest rates remain at historic lows. Financialization of savings is propelling investment in equities. With 4.7% of Indian household assets in equity, as against ~45% in USA, the Indian retail investor's increasing influence in the stock markets is just a preview of what is yet to come.

BMI Research estimates that India's household spending will exceed $3 trillion as disposable income rises by a compounded 14.6% annually until 2027. By then, a projected 25.8% of Indian households will reach $10,000 in annual disposable income. The Indian consumer market is expected to become the world's third largest by 2027.

Leading a new globalization

Indians are not only filling the gap in the domestic markets but are also turning to the rest of the world. In 2023, Indian conglomerate Essar Group kicked off a $4 billion project in Saudi Arabia to build a low-carbon steel plant. In the same year, Tata Sons announced plans to establish a global battery cell gigafactory in the UK with a capacity to produce 40GW of cells annually, with an investment of over $4.38 billion. In 2022, Ola Electric, the ride-hailing company’s electric vehicle subsidiary, announced its plans to establish Ola Futurefoundry, a global hub for advanced engineering and vehicle design in the UK, investing $100 million over the next five years.

India Inc. appears well positioned to become a powerful foreign investor into many countries around the world. India's overseas direct investment (equity and debt) has averaged $16 billion annually for the past three years (the 10-year average was $13 billion). Singapore was the top investment destination, followed by the US and the UK. In fact, as of 2023, India maintained its spot as the second-largest source of FDI (Foreign Direct Investments) projects for the UK, where it invested in 99 projects and generated around 4,800 jobs3.

Among the numerous Indian investors into the UK is a Mumbai-based entrepreneur named Sanjiv Mehta. Sanjiv acquired control of the long defunct East India Company in 2010 and relaunched it as a luxury lifestyle business. With backing from the Mahindra Group, this multinational restart aspires to source from India and retail around the world. If you were looking for any signs that the pendulum of globalization has turned full circle, look no further!

1 The chart on foreign shareholding across the Indian market includes shareholding by foreign controlling shareholders as well as institutional investors

2 Source: ICICI Securities

3 Source: UK Government